In Kargil, Dr Basu was placed inside a room with thick tin sheets serving as the roof over a false ceiling made of compact board. In one corner of the roof was a jagged hole through which the sky was visible. The first, Dr Basu, operated upon was a 21-year-old sepoy, who had a small splinter penetrated in his left armpit. As the author writes that his first operation lasted for only fifteen minutes, but it “seemed like a very long time.”

There have been numerous written and unwritten accounts of India’s first-ever televised war, commonly referred to as the Kargil War. However, rarely do any of these manuscripts shed light on the human side of India's contemporary war tragedy.

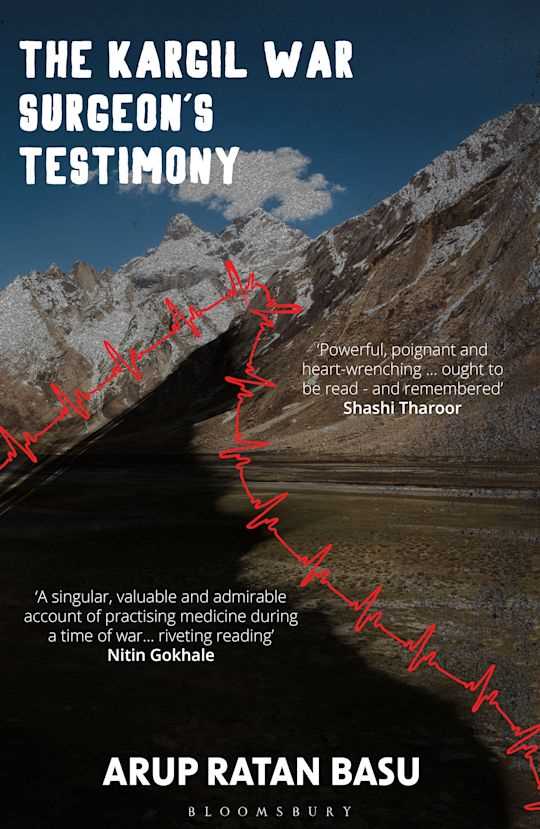

‘The Kargil War Surgeon’s Testimony’ (Bloomsbury) by the Indian Army’s Dr Arup Ratan Basu focuses on the human story of the war as experienced by a doctor.

Dr Basu had brought a notebook from the Kargil town bazaar to note his experiences during his stay in Kargil, and despite his gruelling work at the hospital, he managed to note most of the important events of the war.

In December 1998, Dr Basu qualified as a surgeon in the Indian Army Medical Corps and was immediately sent to a field hospital in the Kashmir valley. After being posted in an army hospital in the Pattan area, he was immediately instructed to move to Kargil, where the action was already underway.

In Kargil, Dr Basu was placed inside a room with thick tin sheets serving as the roof over a false ceiling made of compact board. In one corner of the roof was a jagged hole through which the sky was visible. The first, Dr Basu, operated upon was a 21-year-old sepoy, who had a small splinter penetrated in his left armpit. As the author writes that his first operation lasted for only fifteen minutes, but it “seemed like a very long time.”

An interesting character the author talks about in the book is Dr Kachu Hussain, a local experienced doctor. Dr Kachu was a regular at the army field hospital, helping out the army doctors whenever there was a need or an emergency, as he was working in a nearby hospital. However, Dr Basu was instructed “not to talk to Dr Kachu casually” and “keep the conversation with Dr Kachu purely professional.”

The author says that these instructions were given because the military intelligence had overheard a phone conversation in which a woman’s voice, someone from Kargil, was communicating with someone in Pakistan.

Shockingly for the author, Dr Kachu’s wife was the daughter of a retired Pakistani brigadier, and there was strong suspicion that she may have been the person giving information to the Pakistani Army about the Indian Army’s ammo dump, which was bombed just a few days back. However, the author does not continue with this story, and it remains unclear whether Dr Kachu and his wife were working at Pakistan’s behest or not.

The author has also given a graphic description of Captain Saurav Kalia, whose body was handed over to the post near Kaksar. An army officer told Dr Basu that he had never seen such mutilated bodies, their nails had been pulled out, their earlobes cut away, their eardrum punctured, their eyes gouged out, and their bones broken, even their pensis were cut off.

Captain Saurav Kalia’s wounds were old, indicating that these injuries were inflicted on them while they were alive, and his team was shot from close range.

Crediting Major General Mohinder Puri, who was in command of operations in the Drass sector, it is noted that he had already raised a concern regarding the remote possibility of a Pakistani attack over the Line of Control north of the Kargil sector before the events of Kargil.

However, it has not been given too much importance as the idea of a Pakistani attack on such heights was considered quite improbable. But when Major General Puri’s fears were proven true, he was tasked to lead the Indian response, as military authorities were impressed that he had foreseen the problem.

Writes Dr Basu, that when the news reached New Delhi, there was a panicked reaction and more battalions were sent to Karigl. Soldiers were rapidly deployed to the heights, at over 15,000 feet above sea level.

However, most of the soldiers did not even have proper snow protection, such as boots and jackets, while others had damaged boots – rats had eaten through them and left holes in them when they were in storage. Even then, there was no proper plan in place for replenishing essentials such as food and communication equipment.

“It appeared that commanders were somewhat disconnected from the ground realities of the region. The soldiers and officers were ordered to carry out unrelaitic tasks. Were we caught off guard by the deceitful Pakistani ploy? Or was it just a knee-jerk reaction, with order given without being thought through?” Dr Basu writes in chapter 10 titled ‘A Feat of Bullets’.

The author has also written about the Bollywood celebrities who visited the field army hospital to boost the morale of the troops, and among the celebrities, Javed Akhtar, Shabana Azmi and Vinod Khanna were genuinely concerned about the wounded soldiers, while others were casual about the entire episode.

“Salman Khan kept cracking silly jokes throughout the visit. He wasn’t even sure whether he was in Kargil, Draa or Leh. I don’t think it made any difference to him at all. Raveen Tondon kept repeating the same statement to each patient: ‘Hello bhaiya, how are you? Can you recognise me? I am Raveena.’ When she said this to a semi-unconscious patient, the patient just closed his eyes,” write Dr Basu in his 16 chapter titled ‘Celebrities’.

Dr Basu informs the readers that Javed Jaffrey tried to impress the hospital staff with his breakdance, and Pooja Batra looked quite uninterested in the whole affair, and she seems keen to leave.

‘The Kargil War Surgeon’s Testimony’ can be aptly summed up in the words of British Conservative politician and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain: “In war, whichever side may call itself the victor, there are no winners, but all are losers.”

Email : daanishinterview@gmail.com

In Kargil, Dr Basu was placed inside a room with thick tin sheets serving as the roof over a false ceiling made of compact board. In one corner of the roof was a jagged hole through which the sky was visible. The first, Dr Basu, operated upon was a 21-year-old sepoy, who had a small splinter penetrated in his left armpit. As the author writes that his first operation lasted for only fifteen minutes, but it “seemed like a very long time.”

There have been numerous written and unwritten accounts of India’s first-ever televised war, commonly referred to as the Kargil War. However, rarely do any of these manuscripts shed light on the human side of India's contemporary war tragedy.

‘The Kargil War Surgeon’s Testimony’ (Bloomsbury) by the Indian Army’s Dr Arup Ratan Basu focuses on the human story of the war as experienced by a doctor.

Dr Basu had brought a notebook from the Kargil town bazaar to note his experiences during his stay in Kargil, and despite his gruelling work at the hospital, he managed to note most of the important events of the war.

In December 1998, Dr Basu qualified as a surgeon in the Indian Army Medical Corps and was immediately sent to a field hospital in the Kashmir valley. After being posted in an army hospital in the Pattan area, he was immediately instructed to move to Kargil, where the action was already underway.

In Kargil, Dr Basu was placed inside a room with thick tin sheets serving as the roof over a false ceiling made of compact board. In one corner of the roof was a jagged hole through which the sky was visible. The first, Dr Basu, operated upon was a 21-year-old sepoy, who had a small splinter penetrated in his left armpit. As the author writes that his first operation lasted for only fifteen minutes, but it “seemed like a very long time.”

An interesting character the author talks about in the book is Dr Kachu Hussain, a local experienced doctor. Dr Kachu was a regular at the army field hospital, helping out the army doctors whenever there was a need or an emergency, as he was working in a nearby hospital. However, Dr Basu was instructed “not to talk to Dr Kachu casually” and “keep the conversation with Dr Kachu purely professional.”

The author says that these instructions were given because the military intelligence had overheard a phone conversation in which a woman’s voice, someone from Kargil, was communicating with someone in Pakistan.

Shockingly for the author, Dr Kachu’s wife was the daughter of a retired Pakistani brigadier, and there was strong suspicion that she may have been the person giving information to the Pakistani Army about the Indian Army’s ammo dump, which was bombed just a few days back. However, the author does not continue with this story, and it remains unclear whether Dr Kachu and his wife were working at Pakistan’s behest or not.

The author has also given a graphic description of Captain Saurav Kalia, whose body was handed over to the post near Kaksar. An army officer told Dr Basu that he had never seen such mutilated bodies, their nails had been pulled out, their earlobes cut away, their eardrum punctured, their eyes gouged out, and their bones broken, even their pensis were cut off.

Captain Saurav Kalia’s wounds were old, indicating that these injuries were inflicted on them while they were alive, and his team was shot from close range.

Crediting Major General Mohinder Puri, who was in command of operations in the Drass sector, it is noted that he had already raised a concern regarding the remote possibility of a Pakistani attack over the Line of Control north of the Kargil sector before the events of Kargil.

However, it has not been given too much importance as the idea of a Pakistani attack on such heights was considered quite improbable. But when Major General Puri’s fears were proven true, he was tasked to lead the Indian response, as military authorities were impressed that he had foreseen the problem.

Writes Dr Basu, that when the news reached New Delhi, there was a panicked reaction and more battalions were sent to Karigl. Soldiers were rapidly deployed to the heights, at over 15,000 feet above sea level.

However, most of the soldiers did not even have proper snow protection, such as boots and jackets, while others had damaged boots – rats had eaten through them and left holes in them when they were in storage. Even then, there was no proper plan in place for replenishing essentials such as food and communication equipment.

“It appeared that commanders were somewhat disconnected from the ground realities of the region. The soldiers and officers were ordered to carry out unrelaitic tasks. Were we caught off guard by the deceitful Pakistani ploy? Or was it just a knee-jerk reaction, with order given without being thought through?” Dr Basu writes in chapter 10 titled ‘A Feat of Bullets’.

The author has also written about the Bollywood celebrities who visited the field army hospital to boost the morale of the troops, and among the celebrities, Javed Akhtar, Shabana Azmi and Vinod Khanna were genuinely concerned about the wounded soldiers, while others were casual about the entire episode.

“Salman Khan kept cracking silly jokes throughout the visit. He wasn’t even sure whether he was in Kargil, Draa or Leh. I don’t think it made any difference to him at all. Raveen Tondon kept repeating the same statement to each patient: ‘Hello bhaiya, how are you? Can you recognise me? I am Raveena.’ When she said this to a semi-unconscious patient, the patient just closed his eyes,” write Dr Basu in his 16 chapter titled ‘Celebrities’.

Dr Basu informs the readers that Javed Jaffrey tried to impress the hospital staff with his breakdance, and Pooja Batra looked quite uninterested in the whole affair, and she seems keen to leave.

‘The Kargil War Surgeon’s Testimony’ can be aptly summed up in the words of British Conservative politician and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain: “In war, whichever side may call itself the victor, there are no winners, but all are losers.”

Email : daanishinterview@gmail.com

© Copyright 2023 brighterkashmir.com All Rights Reserved. Quantum Technologies