During a time characterized by the rise of identity politics and majoritarian nationalism, which wishes to create a ‘Hindu’ community with caste divisions and hierarchies intact, the resurgence of Periyar E.V. Ramasamy's radical thought is nothing less than an ethical imperative.

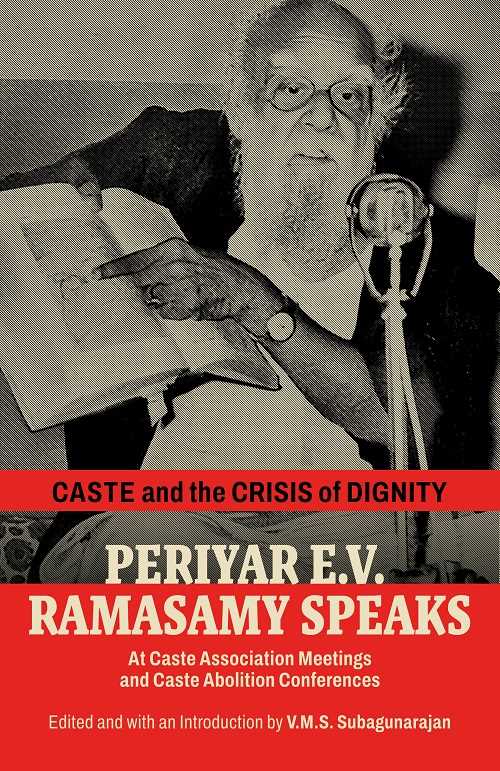

This new volume, Caste and the Crisis of Dignity: Periyar E.V. Ramasamy Speaks (Speaking Tiger), compiled and introduced by V.M.S. Subagunarajan, forms an important archive of Periyar’s lifelong campaign against inherited inequality, presenting the multi-pronged strategy one sought for the annihilation of caste. It goes further to forcefully remind us that the fight for social justice fundamentally is one for self-respect.

Periyar, being an avowed non-conformist and atheist, did not offer gentle critique; he offered polemical confrontation. Subagunarajan's introduction aptly frames Periyar's genius as a philosophical intervention masquerading as mass mobilization. It reveals a political practice that is often paradoxical but always driven by an uncompromising vision of human equality.

Centrality of Self-Respect

The core of Periyar's philosophy crystallizes in his deceptively simple yet profoundly radical formulation: "If we truly believe that no one could ever be below us, then we'll realize that there is no one above us either."

This principle, as amply discussed throughout the selected speeches and writings, demolished centuries of social conditioning based on the concepts of karma and purity.

The volume reproduces an article published on 10 January 1926 in his weekly, Kudi Arasu, which is a kind of foundational text of the Self-Respect Movement. Periyar mentioned the tragic duality of the caste system, wherein individuals are simultaneously made to feel that those who "make it possible for us to breathe clean air are inferior to us because of their karma," while being compelled to worship "dishonest, lowly people who live by sucking our blood are superior to us and that we should worship them, as a means to attain ‘moksha'."

The Self-Respect Movement, therefore, was not a political party in the truest sense of the term. It was a movement that directly addressed the internalized humiliation and the false aspiration for elevation that kept the caste edifice standing.

His critique was clear: caste, superstition, and Brahminical privilege were mutually reinforcing pillars of an oppressive social order. The insistence on 'self-respect' among the lower castes and women became the foundational brick for his conception of democracy and equality, placing the movement as one of the most radical contributions to anti-caste thought in 20th-century India.

Paradox of Political Practice

One of the most engaging aspects of Periyar's political journey-and one that the volume explores in depth-is his seeming paradoxical engagement with religious and caste institutions.

An atheist, he was "extremely critical of narrow nationalism and elite suppression of claims for equality," but he simultaneously "spearheaded several movements demanding rights for lower castes to enter temples."

The most famous example of this two-track approach was his role in the Vaikom struggle of 1924–25. This struggle sought to secure the right for lower castes to use the public roads around the Vaikom Mahadeva Temple in Travancore and put an anti-theist at the head of a movement for Hindu civil rights. It wasn't a contradiction; it was just a tactical deployment of his principles.

Periyar knew that in a caste society, even public roads and civic spaces were colonized by religious hierarchy; demanding equal rights to sacred spaces and their environs exposed the lie of Brahminical privilege and self-respect where it was most denied.

His involvement, which earned him the title ‘Vaikom Veerar’ (Hero of Vaikom), showed that though he demanded nothing less than the complete annihilation of religion and caste, he would go to the extent of struggling within the given framework for civil equality to secure immediate dignity for the downtrodden.

Confrontation, as the introduction here suggests, required a certain, impolite form. Periyar's polemical fire, replete with local idioms and laced with sarcasm, was never gratuitous. It was "shaped by the very nature of the edifice he was up against-one that was simultaneously sacred and violent, polite and oppressive." To critique such a system, he felt, required not politeness but confrontation.

Annihilating Caste from Within

Another facet of the strategic nuance of Periyar's campaign was his joining and addressing numerous meetings organized by caste associations. This sounds paradoxical: a lifelong crusader against caste injustice engaging directly with forums specifically constituted to foster particular caste identities.

The book makes it amply clear that this was a conscious and unparalleled attempt at dismantling hierarchies from within. For Periyar, these conferences, which had often been organized by intermediary and subjugated castes, were not sites of legitimation but rather sites for intervention.

He used the platforms to debunk myths, demand self-respect, and confronted those assembled about their own internalized humiliation and their longing for rise within the hierarchical ladder. He asked them to give up both. Through the use of their own platforms, he denied them the solace of celebrating caste even as he made them confront the source of degradation.

Critique of Nationalism

Beyond social reform, the volume goes on to discuss the details of Periyar's political radicalism-represented mainly by his scathing critique of narrow nationalism.

Periyar warned that the political freedom sought by the nationalist elite would merely replace the British Raj with a 'Brahmin Raj', a euphemism for the continuity of social and political domination under a new flag. He carried on an insistent demand for a Dravidian republic as a political form that was untainted by the caste-ridden structures of a monolithic Indian nationalism.

This critique of elite suppression of equality claims using the trope of nationalism makes the book profoundly relevant today. As majoritarian narratives seek to homogenize diverse communities under one cultural banner, Periyar's insistence on self-respect being more important than Swaraj stands as a powerful counter-narrative in urging the reader to prioritize social emancipation over abstract, elite-driven political goals.

The Challenge and Triumph of Translation The task of translating Periyar is not an easy one. His Tamil was famously "rich with local idioms, biting sarcasm and fierce conviction." Much credit goes to V.M.S. Subagunarajan for ensuring that "what is translated here is not just language, but a mode of thinking."

The translation flows with the raw, unvarnished intellectual rigour needed for carrying what Periyar expressed in his original work. In doing so, a new generation of readers across India is able to engage directly with his arguments.

This is an invaluable volume in understanding how Dravidian politics emerged and sustained itself as a relentless campaign against inequality. Periyar was not interested in being remembered as an idol.

He was interested in being understood. It is in that spirit this comprehensive, timely, and critically important volume must be read—a handbook for those committed to making the annihilation of caste not a "dream deferred to a distant utopia, but as an ethical imperative for the present."

Email: daanishinterview@gmail.com