Zardari Babar's memoir humanises Zardari beyond the caricature of a calculating survivor

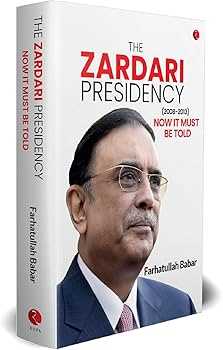

Farhatullah Babar’s insider memoir, ‘The Zardari Presidency: Now It Must Be Told’, published by Rupa Books, is a rare look into the innards of Pakistan's turbulent political theatre between 2008 and 2013.

Babar is a veteran journalist who later turned politician, serving officially as speechwriter to Benazir Bhutto during her first term from 1988 to 1990, and later as her spokesperson in the 1990s.

Later, he served as presidential spokesperson to Asif Ali Zardari. His vantage point allows him to tell the high stakes drama of a presidency that was constantly under siege from the military, the judiciary, the media, and even allies.

This is not a sanitised account. Candid, paradoxical, deeply human in fact, the book portrays Zardari as a calculating pragmatist, every inch a politician, as well as a father bearing grief with quiet strength. Above all, this is an attempt to catalogue the cat and mouse games between Pakistan's elected government and its entrenched deep state.

Democracy: The Best Revenge

In September 2008, when militants had assassinated Benazir Bhutto and captured parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Zardari stepped into his late wife's shoes with the pledge: "Democracy is the best revenge." Few believed he would last. Yet he became the first civilian President to complete a full five year term, and later, remarkably, was re elected.

Babar situates this achievement against relentless conspiracies: Memogate, judicial activism, media hostility, and the all-pervasive shadow of the army. His narrative brings out how Zardari suffered ridicule and jeers, yet steered his way through ominous odds with brazen courage.

Memogate: The Deep State

The most dramatic passages in the book relate to the Memogate scandal of late 2011. Pakistani American businessman Mansoor Ijaz accused the ISI of being a rogue institution, echoing Admiral Mike Mullen’s description of the Haqqani network as “a veritable arm of the Pakistani ISI.” In their eagerness to confront Zardari, the army and ISI chiefs embraced Ijaz’s claims, inadvertently undermining themselves.

By December 2011, Zardari collapsed and sought treatment in Dubai, refusing army medical institutions under General Ashfaq Kayani’s control—a silent indictment of the military.

His defiant return three weeks later coincided with Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani’s bold intervention in Parliament on 23 December, questioning how Osama bin Laden had lived for six years in a military cantonment. Gilani warned that a “state within a state” was unacceptable.

In January 2012, Gilani charged that the chiefs of the army and ISI acted unconstitutionally, removed Defence Secretary General Lodhi and caused military fury. Still, Zardari refused to back down. According to Babar, Zardari came bruised, but his enemies lost more. Memogate went into the history books, and Zardari completed his term.

Achievements Amidst Crises

What makes Babar's account compelling is not so much the chronology of achievements but the manner in which they were wrested from crises.

Removing a dictator (August 2008): When Zardari removed the military ruler from the Presidency peacefully, it was not just procedural but symbolic of rare civilian assertion in Pakistan’s coup ridden history.

Restoration of the 1973 Constitution (April 2010): The 18th Amendment, which transferred powers from the Presidency to Parliament, was nothing short of an act of self limitation. In a political culture where leaders cling to authority, Zardari’s ceding of power was unprecedented, though critics saw it as a tactical rather than principled move.

Revisiting Bhutto's execution (April 2011): The filing of a reference in the Supreme Court to revisit the 1979 verdict against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was both personal and political. It was an attempt to heal a national wound, even as the Court was led by his nemesis, Iftikhar Chaudhry.

Smooth transition of power, 2013: Supervising polls and administering the oath to electoral opponent Nawaz Sharif was more than about the call of duty; it marked a symbolic end to decades of military interruptions.

Laying the groundwork for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor before leaving office was a far-sighted move for CPEC, although its later trajectory is contested.

Babar frames these achievements as acts of resilience. They were not triumphs in a vacuum, but victories carved out in hostile terrain, often at personal and political cost.

Vindication and Re election

The epilogue is striking. In March 2024, the Supreme Court provided a mea culpa of sorts when it ruled that Bhutto’s trial and execution had been “unfair and lacked due process.” Bilawal Bhutto Zardari wept publicly. Weeks later, Zardari was re elected President—a distinction no civilian had earned before.

Nawaz Sharif acknowledged his mistake in chasing Memogate. Saifur Rehman, hitherto the tormentor of Zardari, begged forgiveness. In his second term, Zardari signed the 26th Amendment to thwart judicial politicisation, while his bête noire Iftikhar Chaudhry faded into obscurity. Still, the military seemed unfazed and continued its dalliance with politics.

Humanising

Zardari Babar's memoir humanises Zardari beyond the caricature of a calculating survivor: he emerges as a father grieving his children's loss, a friend loyal to a fault, a leader who bore contempt with stoicism. His self awareness-acknowledging that he was no match for Benazir-adds poignancy.

This dimension makes the book more than political history; it is a study of resilience, grief, and paradox. Style and Significance Babar’s prose is direct, sometimes raw, but anchored on dates, names and events. His vantage point lends authenticity, though critics could question bias.

Yet the book’s significance lies in documenting Pakistan’s hybrid democracy: elected governments perpetually ceding space to unelected institutions. It reminds us that democracy in Pakistan is always fragile, contested, and haunted by its deep state.

Yet it also shows the resilience and defiance that carve out space for civilian authority.

Tailpiece

Farhatullah Babar, The Zardari Presidency: Now It Must Be Told, is essential reading for those who would understand the democratic struggles of Pakistan between 2008 and 2013.

It chronicles how a man derided as accidental defied odds, completed his term and was re elected. It is not a tale of unblemished heroism.

It is an honest and paradoxical story of a presidency that braved treacherous waters, withstood nothing less than relentless attacks, and left behind a legacy that continues to define Pakistan.

Email:--------------------------------daanishinterview@gmail.com

Zardari Babar's memoir humanises Zardari beyond the caricature of a calculating survivor

Farhatullah Babar’s insider memoir, ‘The Zardari Presidency: Now It Must Be Told’, published by Rupa Books, is a rare look into the innards of Pakistan's turbulent political theatre between 2008 and 2013.

Babar is a veteran journalist who later turned politician, serving officially as speechwriter to Benazir Bhutto during her first term from 1988 to 1990, and later as her spokesperson in the 1990s.

Later, he served as presidential spokesperson to Asif Ali Zardari. His vantage point allows him to tell the high stakes drama of a presidency that was constantly under siege from the military, the judiciary, the media, and even allies.

This is not a sanitised account. Candid, paradoxical, deeply human in fact, the book portrays Zardari as a calculating pragmatist, every inch a politician, as well as a father bearing grief with quiet strength. Above all, this is an attempt to catalogue the cat and mouse games between Pakistan's elected government and its entrenched deep state.

Democracy: The Best Revenge

In September 2008, when militants had assassinated Benazir Bhutto and captured parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Zardari stepped into his late wife's shoes with the pledge: "Democracy is the best revenge." Few believed he would last. Yet he became the first civilian President to complete a full five year term, and later, remarkably, was re elected.

Babar situates this achievement against relentless conspiracies: Memogate, judicial activism, media hostility, and the all-pervasive shadow of the army. His narrative brings out how Zardari suffered ridicule and jeers, yet steered his way through ominous odds with brazen courage.

Memogate: The Deep State

The most dramatic passages in the book relate to the Memogate scandal of late 2011. Pakistani American businessman Mansoor Ijaz accused the ISI of being a rogue institution, echoing Admiral Mike Mullen’s description of the Haqqani network as “a veritable arm of the Pakistani ISI.” In their eagerness to confront Zardari, the army and ISI chiefs embraced Ijaz’s claims, inadvertently undermining themselves.

By December 2011, Zardari collapsed and sought treatment in Dubai, refusing army medical institutions under General Ashfaq Kayani’s control—a silent indictment of the military.

His defiant return three weeks later coincided with Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani’s bold intervention in Parliament on 23 December, questioning how Osama bin Laden had lived for six years in a military cantonment. Gilani warned that a “state within a state” was unacceptable.

In January 2012, Gilani charged that the chiefs of the army and ISI acted unconstitutionally, removed Defence Secretary General Lodhi and caused military fury. Still, Zardari refused to back down. According to Babar, Zardari came bruised, but his enemies lost more. Memogate went into the history books, and Zardari completed his term.

Achievements Amidst Crises

What makes Babar's account compelling is not so much the chronology of achievements but the manner in which they were wrested from crises.

Removing a dictator (August 2008): When Zardari removed the military ruler from the Presidency peacefully, it was not just procedural but symbolic of rare civilian assertion in Pakistan’s coup ridden history.

Restoration of the 1973 Constitution (April 2010): The 18th Amendment, which transferred powers from the Presidency to Parliament, was nothing short of an act of self limitation. In a political culture where leaders cling to authority, Zardari’s ceding of power was unprecedented, though critics saw it as a tactical rather than principled move.

Revisiting Bhutto's execution (April 2011): The filing of a reference in the Supreme Court to revisit the 1979 verdict against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was both personal and political. It was an attempt to heal a national wound, even as the Court was led by his nemesis, Iftikhar Chaudhry.

Smooth transition of power, 2013: Supervising polls and administering the oath to electoral opponent Nawaz Sharif was more than about the call of duty; it marked a symbolic end to decades of military interruptions.

Laying the groundwork for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor before leaving office was a far-sighted move for CPEC, although its later trajectory is contested.

Babar frames these achievements as acts of resilience. They were not triumphs in a vacuum, but victories carved out in hostile terrain, often at personal and political cost.

Vindication and Re election

The epilogue is striking. In March 2024, the Supreme Court provided a mea culpa of sorts when it ruled that Bhutto’s trial and execution had been “unfair and lacked due process.” Bilawal Bhutto Zardari wept publicly. Weeks later, Zardari was re elected President—a distinction no civilian had earned before.

Nawaz Sharif acknowledged his mistake in chasing Memogate. Saifur Rehman, hitherto the tormentor of Zardari, begged forgiveness. In his second term, Zardari signed the 26th Amendment to thwart judicial politicisation, while his bête noire Iftikhar Chaudhry faded into obscurity. Still, the military seemed unfazed and continued its dalliance with politics.

Humanising

Zardari Babar's memoir humanises Zardari beyond the caricature of a calculating survivor: he emerges as a father grieving his children's loss, a friend loyal to a fault, a leader who bore contempt with stoicism. His self awareness-acknowledging that he was no match for Benazir-adds poignancy.

This dimension makes the book more than political history; it is a study of resilience, grief, and paradox. Style and Significance Babar’s prose is direct, sometimes raw, but anchored on dates, names and events. His vantage point lends authenticity, though critics could question bias.

Yet the book’s significance lies in documenting Pakistan’s hybrid democracy: elected governments perpetually ceding space to unelected institutions. It reminds us that democracy in Pakistan is always fragile, contested, and haunted by its deep state.

Yet it also shows the resilience and defiance that carve out space for civilian authority.

Tailpiece

Farhatullah Babar, The Zardari Presidency: Now It Must Be Told, is essential reading for those who would understand the democratic struggles of Pakistan between 2008 and 2013.

It chronicles how a man derided as accidental defied odds, completed his term and was re elected. It is not a tale of unblemished heroism.

It is an honest and paradoxical story of a presidency that braved treacherous waters, withstood nothing less than relentless attacks, and left behind a legacy that continues to define Pakistan.

Email:--------------------------------daanishinterview@gmail.com

© Copyright 2023 brighterkashmir.com All Rights Reserved. Quantum Technologies