The letter further argued: “The Urdu Academy exists for the minority community; granting a platform to such an atheist and critic of religion will wound the sentiments of the community.” It demanded: “He should not be made chief guest; instead, someone ‘worthy and faithful’ should be invited, irrespective of religion.” The letter also carried a threat: “If our objection is not heeded, there will be ‘democratic’ agitations like the Taslima Nasreen incident of 2007; we had previously forced her to leave Bengal through such a movement.”

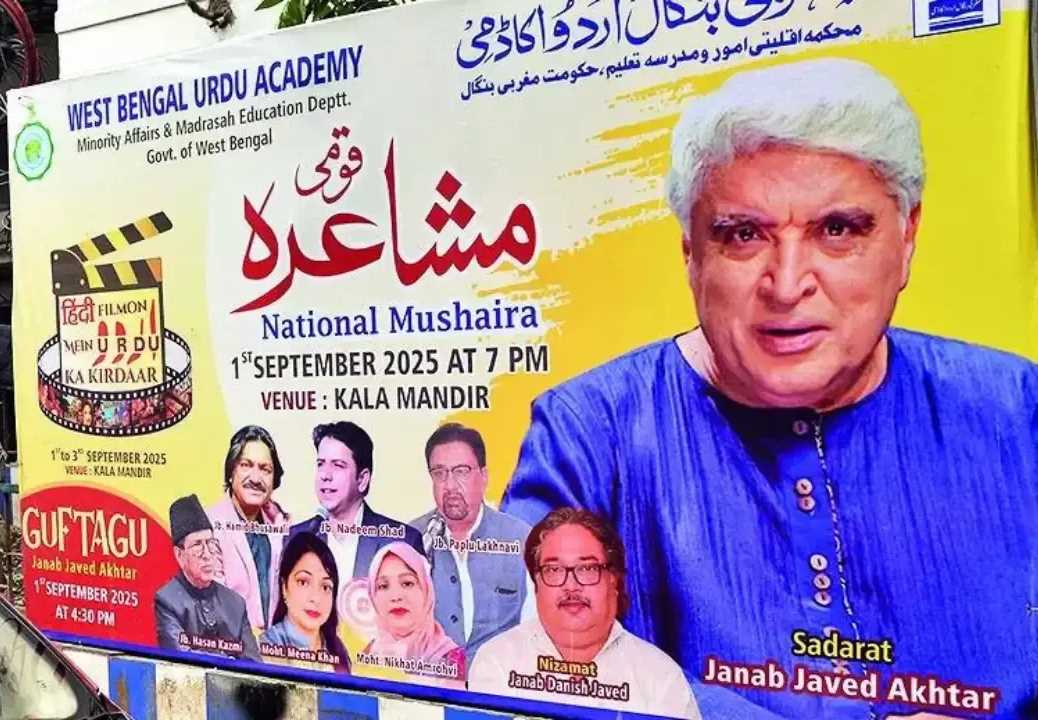

Between August 31 and September 3, at the Academy Office, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Road, Kala Mandir, Kolkata, a program had been scheduled on the theme “The Contribution of Urdu to Hindi Cinema.” The event was to include a mushaira (poetic symposium), film screenings, and seminars. The chief presiding guest of the mushaira and the primary invitee was the renowned lyricist, poet, and scriptwriter Javed Akhtar, while filmmaker Muzaffar Ali was invited as another guest of honor. Posters and banners of timeless classics such as Mughal-e-Azam, Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool, and Umrao Jaan had already been put up at the venue. Initially, the Urdu Academy was enthusiastic about the program, but as opposition grew and the fear of unrest escalated, it suddenly cancelled the event.

The official statement cited “unavoidable circumstances” and “security reasons” for the decision. The government feared the possibility of an attack on Akhtar, incidents of ink-throwing, disturbances, or other violent acts. In her official declaration, Urdu Academy Secretary Nuzhat Zainab announced: “Due to unavoidable circumstances, the program ‘Urdu in Hindi Cinema,’ scheduled between August 31 and September 3, is hereby postponed.”

The perspective of the Bengal government on this matter is quite revealing. Following protests by Islamic fundamentalist organizations, the government, mindful of the upcoming elections, chose not to antagonize any section and therefore opted for postponement. With the 2026 Assembly elections in view, the Mamata Banerjee government wished to avoid any form of religious conflict or violence. Both the government and TMC leaders refrained from making public statements on the matter. Several leaders declined to comment, while others supported the suspension of the event in order to avoid embarrassment from an “unpleasant incident” such as an ink attack and to prevent a situation where they might have to request Javed Akhtar not to attend.

Undeniably, this has damaged the liberal and secular image of Bengal that had been nurtured under leftist governments. The government, by succumbing to the pressure of fundamentalists, has compromised on the values of literature and freedom. This controversy has placed freedom of expression, literature, and politics simultaneously at the center of debate.

The Islamic organizations opposing Javed Akhtar prominently include Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (Bengal Unit), Jamiat Ulema Kolkata, and Wahyain Foundation. The Jamiat Ulema claimed that “Javed Akhtar has spoken very badly and insultingly against Islam, Muslims, and Allah.” Jamiat Ulema Kolkata’s General Secretary, Zillur Rahman Arif, publicly declared: “This man (Javed Akhtar) is not a human being but a devil in human form.” In a letter, the Vice President of Jamiat alleged that “he (Javed Akhtar) is anti-religion and is habitually inclined to insult followers of other faiths.”

The letter further argued: “The Urdu Academy exists for the minority community; granting a platform to such an atheist and critic of religion will wound the sentiments of the community.” It demanded: “He should not be made chief guest; instead, someone ‘worthy and faithful’ should be invited, irrespective of religion.” The letter also carried a threat: “If our objection is not heeded, there will be ‘democratic’ agitations like the Taslima Nasreen incident of 2007; we had previously forced her to leave Bengal through such a movement.”

Another Muslim fundamentalist organization, the Wahyain Foundation, issued a statement claiming that inviting Javed Akhtar would have a “negative influence on the youth.” They even challenged him to participate in a debate on religion. Jamiat Ulema (Bengal Unit) General Secretary Mufti Abdus Salam registered his protest, saying: “We have no objection to his being an atheist, but he has repeatedly made insulting remarks on religion—this is why we object.”

Jamiat Ulema Kolkata General Secretary Zillur Rahman Arif, in his inflammatory remarks, reiterated: “…This man is a devil… do not include him in the program.” Given the substantial minority population in Bengal and the government’s willingness to bend before these organizations, the event was called off under the pretext of “unavoidable circumstances.” The Muslim fundamentalist organizations, considering this cancellation as a victory for their objection, have been celebrating.

Some newspapers have carried Javed Akhtar’s statement in which he clearly said: “I am an atheist. My name ‘Javed Akhtar’ has nothing to do with Islam; both words are Persian. Only in India are names linked to religion.” He further added: “I am abused by extremists on both sides—Hindu and Muslim; when both abuse me, I take it as a sign that I am doing something right.”

Referring to the non-religious, anti-superstition, egalitarian tendencies, scientific outlook, and criticism of organized religion that have been inherent in Urdu poetry and literature since its inception, he expressed his affection for Kolkata. He wrote: “This city is liberal and progressive. I regard the ‘Boi Mela’ as a pilgrimage—thousands of people come only for books; this reassures me that the world is not as bad as it seems.”

In this way, Javed Akhtar openly responded to the allegations made by his opponents. He stated in clear terms that he is an atheist and has never concealed this fact. According to him, throughout his life he has faced attacks from fundamentalists of both sides—Hindu and Muslim. His argument was that he was not going to the festival to deliver a lecture on religion, but rather to discuss the role of Urdu in literature and cinema.

Praising Kolkata and its progressive tradition, Akhtar said that this city has always been known for intellectual debate, open-mindedness, and cultural diversity. He expressed disappointment that if even here freedom of expression is being strangled, it is a matter of concern for the entire country. In his view, the real reason for the opposition is personal hatred and a fundamentalist mindset, not concern for literature or society.

Intellectuals, Urdu enthusiasts, social activists, organizations, and leftist progressive student bodies, including SFI, have reacted across the country. Many writers and thinkers have also stated that the Urdu language is not the monopoly of any single religion. It is a shared cultural heritage that has produced stalwarts like Ghalib, Faiz, and Sahir Ludhianvi.

From the literary field, Mudara Patheria, Zeeshan Majeed, Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, Tayyab Ahmad Khan, Zahir Anwar, Palash Chaturvedi, Mueen-ud-din Hamid, Smita Chandra, Spandan Roy Biswas, Naveen Vohra, Zahid Hussain, Abhay Phadnis, and other intellectuals strongly criticized the development. Collectively, they wrote a letter to the Chief Minister as “Urdu lovers and liberal Muslims,” criticizing Mamata Banerjee’s stance and objecting that the West Bengal Urdu Academy (which does not even have the word ‘Muslim’ in its name) withdrew the invitation only to appease fundamentalists.

Their letter stated: “Linking Urdu with ‘Muslimness’ undermines the secular nature of the language; the Academy is a cultural institution, not a religious one. The poet’s personal belief or atheism was placed above the subject (Urdu in Hindi Cinema), which had no relation to religion. Now any institution can easily be forced to reverse decisions under the pretext that ‘religion is in danger.’ In liberal Bengal, under your chief ministership, this is disappointing; we expect the protection of freedom of expression.”

Ghazala Yasmin, associated with the Governing Body of the Urdu Academy and Aliah University, stated: “Urdu is an Indian language—without any religious affiliation—it should be celebrated for its cultural, aesthetic, and literary excellence; not hijacked by narrow religious fundamentalism.” Expressing disappointment over the postponement, she also voiced hope: “We will later hold the event with even more diversity and broader reach.”

Scientist, writer, and filmmaker Gauhar Raza called the cancellation of the event “extremely worrying and unacceptable,” stating: “Fundamentalists—Hindu and Muslim alike—want to silence the voice of rationality. Javed Akhtar is a strong, clear, loud, and creative voice of reason. Fundamentalist forces exist within every religion. Their aim is to divide society, not to unite it.”

The Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) also issued a press release condemning the cancellation and described the issue as a threat to democratic rights and freedom of expression.

Human rights and social activist Shabnam Hashmi wrote on her X handle opposing the legitimization of platforms that run under the slogan of “Muslim Right.” She warned: “This is just the beginning—the danger is that fundamentalism will be legitimized.” She further stated that if necessary, she herself would organize a separate event in Kolkata.

Her words were categorical: “India is neither a Hindu nation nor an Islamic one; atheists too have the right to live and speak—indeed, even in religion-dominated states, non-believers exist.”

Kolkata-based researcher Sabir Ahmed says: “There must be some freedom of expression; whether one is religious or atheist is a matter of personal choice. Cancelling a program because of remarks made in some other context is intolerance; differences of opinion must be tolerated.”

Social activist Manzar Jameel added: “If there was an objection to his views, then there should have been debate or contestation at the event itself—it is clear that was not the real objective. Writers, poets, and artists inhabit a different universe; they cannot be confined within ‘narrow definitions.’” He also said: “The Urdu Academy is a literary body, not a madrasa or religious institution; let there be debate, not boycott or threats.” Political scientist Maidul Islam described the incident as “a result of electoral compulsions, sending the wrong message to the public, and a blow to liberal values.” People associated with social unity campaigns wrote that such decisions “strengthen distance and communalization between communities.”

Dr. Shamsuddin Tamboli, President of the Muslim Satya Shodhak Mandal, strongly supported Javed Akhtar and sharply criticized the West Bengal government for cancelling the program. He wrote that India is a secular country, yet it is unfortunate that the meaning of religious freedom guaranteed to Indian citizens under the Constitution is still not properly understood. The true meaning of freedom of religion, he argued, is not only the freedom to practice a faith but also the freedom to reject it and to critically examine it.

Janwadi Lekhak Sangh described the cancellation of Javed Akhtar’s literary festival as “cultural hooliganism,” calling it a direct attack on freedom of expression, the cultural heritage of Urdu, and democracy itself. In its statement, the Association termed the decision cowardly, declaring that the Bengal government and the Urdu Academy had abdicated their responsibility to the people and surrendered before fundamentalist groups. It further stated that the attempt to bind the Urdu language in religious shackles is tantamount to murdering India’s composite Ganga-Jamuni culture. Fundamentalist forces, it said, whether in the name of any religion, ultimately aim to prevent people from thinking, questioning, and speaking. “This is a fascist assault, and the only answer is cultural resistance and mass movements.” The Association has called for nationwide protests against the incident.

In states ruled by the BJP’s Hindutva-driven ideology, attacks on book fairs, discussions, and seminars have become routine. Kolkata, long regarded as the intellectual capital of India, has always been a hub of literature, art, and music. Its book fairs and theatre festivals are internationally renowned. The city has historically been considered a bastion of intellectual debate and progressive thought.

Its book fairs, cultural institutions, and literary discourses have symbolized openness and diversity. Its book fairs, film festivals, and literary conferences have won both national and international recognition. Against this backdrop, the present incident stands as a symbol of the irony of today’s India. If in such a city a literary event is cancelled under religious pressure, it tarnishes not only Kolkata’s image but also raises questions about India’s democratic tradition. The cancellation of the literature festival is a blemish on this tradition.

When even states like Bengal witness such developments, the larger question is this: in a democracy like India, can a writer, poet, or artist be removed from a platform merely because their ideas make some community uncomfortable? The essence of freedom of expression is precisely that dialogue and debate must continue despite disagreement. Protests, threats, and violence in the name of religious identity in fact weaken the very foundations of the democratic structure. And when the government bows to such pressure, the message conveyed is that fundamentalism has triumphed and free thought has lost.

Across the country today, while fundamentalism and political fear dominate society on one hand, literature, art, and freedom of expression are being increasingly suppressed on the other. This controversy reminds us that if we fail to safeguard freedom of thought, we will lose both our cultural heritage and our democratic values. The politics of religious identity, when combined with the calculations of power, has placed a stranglehold on free thought. The shadow of fundamentalism is deepening here as well. It is ironic that the very city which once carried the banner of freedom of thought is now gripped by fear of books and poetry.

This controversy also raises another crucial question: is Urdu solely the language of the Muslim community? The truth is that Urdu developed as a product of the shared culture of both Hindus and Muslims. From film songs and poetry to the freedom struggle, Urdu has woven Indian society together. The language not only enriched literature but also gave depth to Indian cinema. Lyricists like Sahir Ludhianvi, Shakeel Badayuni, Ali Sardar Jafri, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi, Gulzar, and Javed Akhtar gave Hindi films a poetic dimension.

To claim that Urdu belongs to a single religion is to do injustice to its shared heritage. This decision was not only a matter of law and order but also an outcome of appeasement politics. Urdu is neither exclusively the language of Muslims nor the property of any one community. From Delhi, Lucknow, and Hyderabad to Kolkata, it has been the language of a shared culture. The history of Hindi cinema is incomplete without Urdu. From Mughal-e-Azam to Pyaasa and even to contemporary songs like Zindagi Gulzar Hai, the delicacy and beauty of Urdu words have always shone through. This language gave Indian cinema the magic that won admiration worldwide.

Therefore, the festival on “Urdu in Hindi Cinema” was not just a cultural program; it was an occasion to celebrate this shared heritage. Its cancellation is also a blow to that collective culture. Today, in the climate of religious fundamentalist politics and society, freedom of expression stands insecure. The pressure of religious organizations, the government’s compromising stance, and the helplessness of intellectuals together prove that combating fundamentalism is becoming increasingly difficult. If we truly want India to symbolize unity in diversity, then we must protect such events.

Email:---------------------------janwadilekhaksangh@gmail.com

The letter further argued: “The Urdu Academy exists for the minority community; granting a platform to such an atheist and critic of religion will wound the sentiments of the community.” It demanded: “He should not be made chief guest; instead, someone ‘worthy and faithful’ should be invited, irrespective of religion.” The letter also carried a threat: “If our objection is not heeded, there will be ‘democratic’ agitations like the Taslima Nasreen incident of 2007; we had previously forced her to leave Bengal through such a movement.”

Between August 31 and September 3, at the Academy Office, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Road, Kala Mandir, Kolkata, a program had been scheduled on the theme “The Contribution of Urdu to Hindi Cinema.” The event was to include a mushaira (poetic symposium), film screenings, and seminars. The chief presiding guest of the mushaira and the primary invitee was the renowned lyricist, poet, and scriptwriter Javed Akhtar, while filmmaker Muzaffar Ali was invited as another guest of honor. Posters and banners of timeless classics such as Mughal-e-Azam, Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool, and Umrao Jaan had already been put up at the venue. Initially, the Urdu Academy was enthusiastic about the program, but as opposition grew and the fear of unrest escalated, it suddenly cancelled the event.

The official statement cited “unavoidable circumstances” and “security reasons” for the decision. The government feared the possibility of an attack on Akhtar, incidents of ink-throwing, disturbances, or other violent acts. In her official declaration, Urdu Academy Secretary Nuzhat Zainab announced: “Due to unavoidable circumstances, the program ‘Urdu in Hindi Cinema,’ scheduled between August 31 and September 3, is hereby postponed.”

The perspective of the Bengal government on this matter is quite revealing. Following protests by Islamic fundamentalist organizations, the government, mindful of the upcoming elections, chose not to antagonize any section and therefore opted for postponement. With the 2026 Assembly elections in view, the Mamata Banerjee government wished to avoid any form of religious conflict or violence. Both the government and TMC leaders refrained from making public statements on the matter. Several leaders declined to comment, while others supported the suspension of the event in order to avoid embarrassment from an “unpleasant incident” such as an ink attack and to prevent a situation where they might have to request Javed Akhtar not to attend.

Undeniably, this has damaged the liberal and secular image of Bengal that had been nurtured under leftist governments. The government, by succumbing to the pressure of fundamentalists, has compromised on the values of literature and freedom. This controversy has placed freedom of expression, literature, and politics simultaneously at the center of debate.

The Islamic organizations opposing Javed Akhtar prominently include Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (Bengal Unit), Jamiat Ulema Kolkata, and Wahyain Foundation. The Jamiat Ulema claimed that “Javed Akhtar has spoken very badly and insultingly against Islam, Muslims, and Allah.” Jamiat Ulema Kolkata’s General Secretary, Zillur Rahman Arif, publicly declared: “This man (Javed Akhtar) is not a human being but a devil in human form.” In a letter, the Vice President of Jamiat alleged that “he (Javed Akhtar) is anti-religion and is habitually inclined to insult followers of other faiths.”

The letter further argued: “The Urdu Academy exists for the minority community; granting a platform to such an atheist and critic of religion will wound the sentiments of the community.” It demanded: “He should not be made chief guest; instead, someone ‘worthy and faithful’ should be invited, irrespective of religion.” The letter also carried a threat: “If our objection is not heeded, there will be ‘democratic’ agitations like the Taslima Nasreen incident of 2007; we had previously forced her to leave Bengal through such a movement.”

Another Muslim fundamentalist organization, the Wahyain Foundation, issued a statement claiming that inviting Javed Akhtar would have a “negative influence on the youth.” They even challenged him to participate in a debate on religion. Jamiat Ulema (Bengal Unit) General Secretary Mufti Abdus Salam registered his protest, saying: “We have no objection to his being an atheist, but he has repeatedly made insulting remarks on religion—this is why we object.”

Jamiat Ulema Kolkata General Secretary Zillur Rahman Arif, in his inflammatory remarks, reiterated: “…This man is a devil… do not include him in the program.” Given the substantial minority population in Bengal and the government’s willingness to bend before these organizations, the event was called off under the pretext of “unavoidable circumstances.” The Muslim fundamentalist organizations, considering this cancellation as a victory for their objection, have been celebrating.

Some newspapers have carried Javed Akhtar’s statement in which he clearly said: “I am an atheist. My name ‘Javed Akhtar’ has nothing to do with Islam; both words are Persian. Only in India are names linked to religion.” He further added: “I am abused by extremists on both sides—Hindu and Muslim; when both abuse me, I take it as a sign that I am doing something right.”

Referring to the non-religious, anti-superstition, egalitarian tendencies, scientific outlook, and criticism of organized religion that have been inherent in Urdu poetry and literature since its inception, he expressed his affection for Kolkata. He wrote: “This city is liberal and progressive. I regard the ‘Boi Mela’ as a pilgrimage—thousands of people come only for books; this reassures me that the world is not as bad as it seems.”

In this way, Javed Akhtar openly responded to the allegations made by his opponents. He stated in clear terms that he is an atheist and has never concealed this fact. According to him, throughout his life he has faced attacks from fundamentalists of both sides—Hindu and Muslim. His argument was that he was not going to the festival to deliver a lecture on religion, but rather to discuss the role of Urdu in literature and cinema.

Praising Kolkata and its progressive tradition, Akhtar said that this city has always been known for intellectual debate, open-mindedness, and cultural diversity. He expressed disappointment that if even here freedom of expression is being strangled, it is a matter of concern for the entire country. In his view, the real reason for the opposition is personal hatred and a fundamentalist mindset, not concern for literature or society.

Intellectuals, Urdu enthusiasts, social activists, organizations, and leftist progressive student bodies, including SFI, have reacted across the country. Many writers and thinkers have also stated that the Urdu language is not the monopoly of any single religion. It is a shared cultural heritage that has produced stalwarts like Ghalib, Faiz, and Sahir Ludhianvi.

From the literary field, Mudara Patheria, Zeeshan Majeed, Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, Tayyab Ahmad Khan, Zahir Anwar, Palash Chaturvedi, Mueen-ud-din Hamid, Smita Chandra, Spandan Roy Biswas, Naveen Vohra, Zahid Hussain, Abhay Phadnis, and other intellectuals strongly criticized the development. Collectively, they wrote a letter to the Chief Minister as “Urdu lovers and liberal Muslims,” criticizing Mamata Banerjee’s stance and objecting that the West Bengal Urdu Academy (which does not even have the word ‘Muslim’ in its name) withdrew the invitation only to appease fundamentalists.

Their letter stated: “Linking Urdu with ‘Muslimness’ undermines the secular nature of the language; the Academy is a cultural institution, not a religious one. The poet’s personal belief or atheism was placed above the subject (Urdu in Hindi Cinema), which had no relation to religion. Now any institution can easily be forced to reverse decisions under the pretext that ‘religion is in danger.’ In liberal Bengal, under your chief ministership, this is disappointing; we expect the protection of freedom of expression.”

Ghazala Yasmin, associated with the Governing Body of the Urdu Academy and Aliah University, stated: “Urdu is an Indian language—without any religious affiliation—it should be celebrated for its cultural, aesthetic, and literary excellence; not hijacked by narrow religious fundamentalism.” Expressing disappointment over the postponement, she also voiced hope: “We will later hold the event with even more diversity and broader reach.”

Scientist, writer, and filmmaker Gauhar Raza called the cancellation of the event “extremely worrying and unacceptable,” stating: “Fundamentalists—Hindu and Muslim alike—want to silence the voice of rationality. Javed Akhtar is a strong, clear, loud, and creative voice of reason. Fundamentalist forces exist within every religion. Their aim is to divide society, not to unite it.”

The Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) also issued a press release condemning the cancellation and described the issue as a threat to democratic rights and freedom of expression.

Human rights and social activist Shabnam Hashmi wrote on her X handle opposing the legitimization of platforms that run under the slogan of “Muslim Right.” She warned: “This is just the beginning—the danger is that fundamentalism will be legitimized.” She further stated that if necessary, she herself would organize a separate event in Kolkata.

Her words were categorical: “India is neither a Hindu nation nor an Islamic one; atheists too have the right to live and speak—indeed, even in religion-dominated states, non-believers exist.”

Kolkata-based researcher Sabir Ahmed says: “There must be some freedom of expression; whether one is religious or atheist is a matter of personal choice. Cancelling a program because of remarks made in some other context is intolerance; differences of opinion must be tolerated.”

Social activist Manzar Jameel added: “If there was an objection to his views, then there should have been debate or contestation at the event itself—it is clear that was not the real objective. Writers, poets, and artists inhabit a different universe; they cannot be confined within ‘narrow definitions.’” He also said: “The Urdu Academy is a literary body, not a madrasa or religious institution; let there be debate, not boycott or threats.” Political scientist Maidul Islam described the incident as “a result of electoral compulsions, sending the wrong message to the public, and a blow to liberal values.” People associated with social unity campaigns wrote that such decisions “strengthen distance and communalization between communities.”

Dr. Shamsuddin Tamboli, President of the Muslim Satya Shodhak Mandal, strongly supported Javed Akhtar and sharply criticized the West Bengal government for cancelling the program. He wrote that India is a secular country, yet it is unfortunate that the meaning of religious freedom guaranteed to Indian citizens under the Constitution is still not properly understood. The true meaning of freedom of religion, he argued, is not only the freedom to practice a faith but also the freedom to reject it and to critically examine it.

Janwadi Lekhak Sangh described the cancellation of Javed Akhtar’s literary festival as “cultural hooliganism,” calling it a direct attack on freedom of expression, the cultural heritage of Urdu, and democracy itself. In its statement, the Association termed the decision cowardly, declaring that the Bengal government and the Urdu Academy had abdicated their responsibility to the people and surrendered before fundamentalist groups. It further stated that the attempt to bind the Urdu language in religious shackles is tantamount to murdering India’s composite Ganga-Jamuni culture. Fundamentalist forces, it said, whether in the name of any religion, ultimately aim to prevent people from thinking, questioning, and speaking. “This is a fascist assault, and the only answer is cultural resistance and mass movements.” The Association has called for nationwide protests against the incident.

In states ruled by the BJP’s Hindutva-driven ideology, attacks on book fairs, discussions, and seminars have become routine. Kolkata, long regarded as the intellectual capital of India, has always been a hub of literature, art, and music. Its book fairs and theatre festivals are internationally renowned. The city has historically been considered a bastion of intellectual debate and progressive thought.

Its book fairs, cultural institutions, and literary discourses have symbolized openness and diversity. Its book fairs, film festivals, and literary conferences have won both national and international recognition. Against this backdrop, the present incident stands as a symbol of the irony of today’s India. If in such a city a literary event is cancelled under religious pressure, it tarnishes not only Kolkata’s image but also raises questions about India’s democratic tradition. The cancellation of the literature festival is a blemish on this tradition.

When even states like Bengal witness such developments, the larger question is this: in a democracy like India, can a writer, poet, or artist be removed from a platform merely because their ideas make some community uncomfortable? The essence of freedom of expression is precisely that dialogue and debate must continue despite disagreement. Protests, threats, and violence in the name of religious identity in fact weaken the very foundations of the democratic structure. And when the government bows to such pressure, the message conveyed is that fundamentalism has triumphed and free thought has lost.

Across the country today, while fundamentalism and political fear dominate society on one hand, literature, art, and freedom of expression are being increasingly suppressed on the other. This controversy reminds us that if we fail to safeguard freedom of thought, we will lose both our cultural heritage and our democratic values. The politics of religious identity, when combined with the calculations of power, has placed a stranglehold on free thought. The shadow of fundamentalism is deepening here as well. It is ironic that the very city which once carried the banner of freedom of thought is now gripped by fear of books and poetry.

This controversy also raises another crucial question: is Urdu solely the language of the Muslim community? The truth is that Urdu developed as a product of the shared culture of both Hindus and Muslims. From film songs and poetry to the freedom struggle, Urdu has woven Indian society together. The language not only enriched literature but also gave depth to Indian cinema. Lyricists like Sahir Ludhianvi, Shakeel Badayuni, Ali Sardar Jafri, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi, Gulzar, and Javed Akhtar gave Hindi films a poetic dimension.

To claim that Urdu belongs to a single religion is to do injustice to its shared heritage. This decision was not only a matter of law and order but also an outcome of appeasement politics. Urdu is neither exclusively the language of Muslims nor the property of any one community. From Delhi, Lucknow, and Hyderabad to Kolkata, it has been the language of a shared culture. The history of Hindi cinema is incomplete without Urdu. From Mughal-e-Azam to Pyaasa and even to contemporary songs like Zindagi Gulzar Hai, the delicacy and beauty of Urdu words have always shone through. This language gave Indian cinema the magic that won admiration worldwide.

Therefore, the festival on “Urdu in Hindi Cinema” was not just a cultural program; it was an occasion to celebrate this shared heritage. Its cancellation is also a blow to that collective culture. Today, in the climate of religious fundamentalist politics and society, freedom of expression stands insecure. The pressure of religious organizations, the government’s compromising stance, and the helplessness of intellectuals together prove that combating fundamentalism is becoming increasingly difficult. If we truly want India to symbolize unity in diversity, then we must protect such events.

Email:---------------------------janwadilekhaksangh@gmail.com

© Copyright 2023 brighterkashmir.com All Rights Reserved. Quantum Technologies