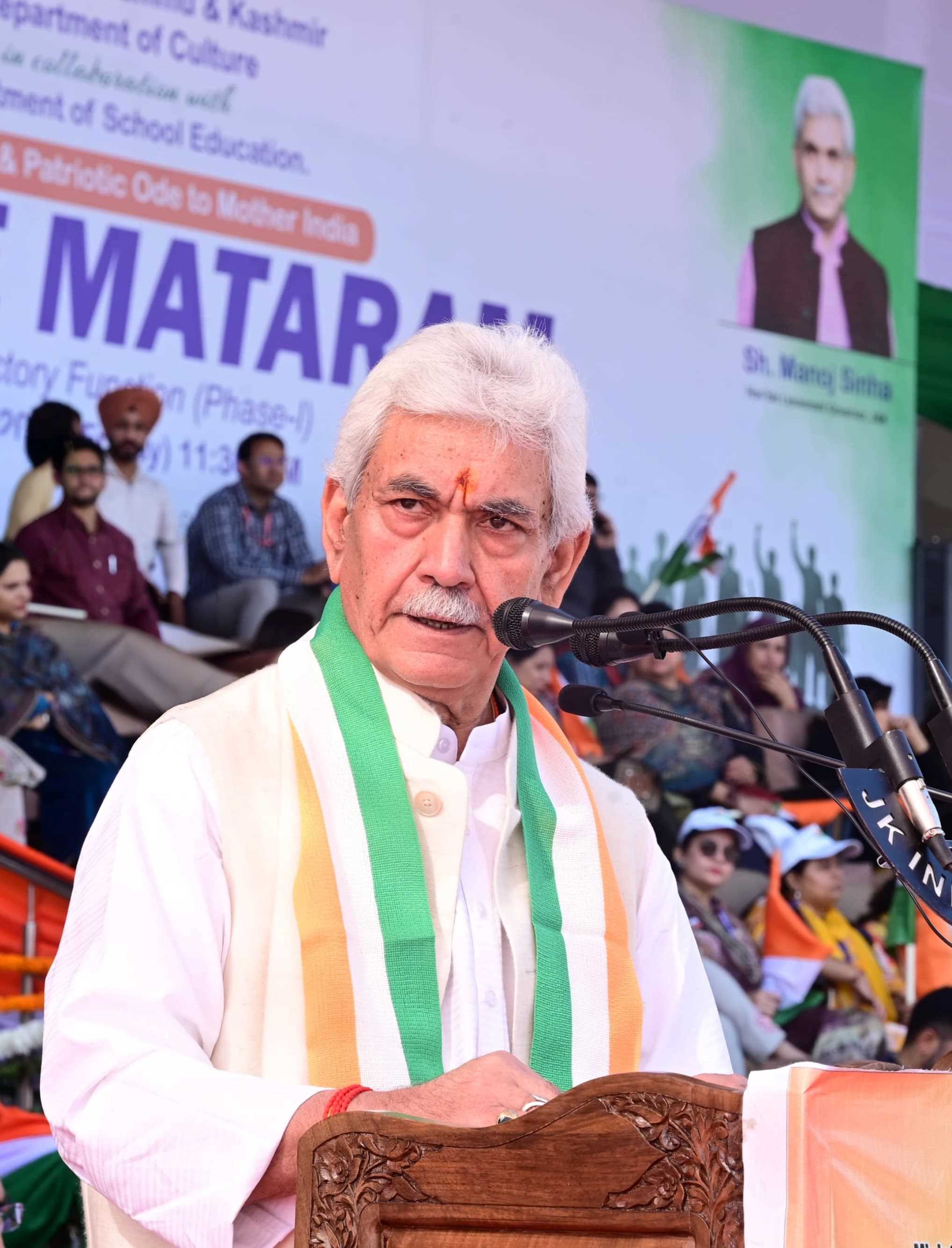

In the years following the abrogation of Article 370, Jammu and Kashmir entered one of the most significant phases of transformation in its modern history. This period has been shaped strongly by the administrative leadership of Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha, who took charge at a time when the region was going through political uncertainty, security challenges, and widespread public apprehension. What emerged over the next few years was a story of stabilization, reform, and rebuilding, driven not by speeches, but by persistent on-ground action.

When Sinha assumed office in August 2020, Jammu and Kashmir had just undergone a major constitutional shift. The old political structures had been dismantled, and there was no elected government in place to address the concerns of the people. Decades of terrorism, bureaucratic corruption, and uneven development had created deep mistrust between citizens and institutions. Many believed that the new administrative setup would struggle to bridge this gap. Yet, Sinha took on this challenge with a distinct style, quiet, focused, and determined.

One of the earliest moves of his tenure was an uncompromising stand against anti-national networks operating from within the government system. For decades, certain pockets within state institutions had been accused of soft separatism or direct links with radical elements. Sinha’s administration acted firmly by terminating over various government employees who were found involved in activities harmful to national security. This decision sent a message that the state would no longer tolerate institutional sabotage masked under government employment. At the same time, it reassured ordinary citizens that the system was finally becoming accountable.

The fight against terrorism also witnessed notable changes. Instead of reacting only through security operations, the administration adopted a more comprehensive approach. Stone-pelting, once a regular feature in the Valley, saw a dramatic decline due to a combination of policing, engagement programmes, and youth-oriented initiatives. Mission Youth, livelihood schemes, sports activities, and targeted counselling created opportunities for young people who had previously found themselves vulnerable to radical influences. The result was a sharp reduction in street violence and an improvement in public confidence.

Parallel to these security reforms, the administration also made major strides in governance. Sinha introduced digital e-filing system which replaced this old time consumed system with digital governance through the introduction of the e-Office, which allowed files to move electronically across departments without geographic delays. This transition saved crores of rupees and drastically increased administrative efficiency.

Digital transformation did not stop there. A wide range of public services, from land records to certificates, grievances, and welfare applications were brought online. For the first time, citizens across rural and urban areas could track their official documents and file requests without relying on intermediaries or political recommendations. Platforms like Apki Zameen Apki Nigrani and JKIGRAMS gave people direct access to governance, reducing corruption and ensuring transparency. Thousands of villages were connected with internet facilities and Common Service Centres, allowing even remote communities to benefit from online services.

Sinha’s tenure also focused strongly on social inclusion, especially for the tribal and nomadic communities who had been historically denied their rights due to the previous legal framework. The introduction of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 in Jammu and Kashmir gave these groups legal ownership of land and forest resources for the first time. Thousands of claims were processed, granting land titles to families who had lived on forest land for generations. Mobile schools, mobile health clinics, transit camps, and welfare programmes supported nomadic groups like Gujjars and Bakerwals, recognizing their unique lifestyle instead of forcing them into rigid administrative structures.

Healthcare emerged as another major pillar of reform. The COVID-19 pandemic became both a challenge and a turning point. Within a span of days, new hospitals were built, oxygen plants were installed across districts, and vaccination campaigns reached even the most remote areas. Modern equipment such as CT scanners, dialysis units, and digital X-rays were placed in district and sub-district hospitals. Ambulance fleets expanded dramatically, and telemedicine services brought specialist care to villages that had long remained disconnected from medical infrastructure. For the first time, health services began to reach people where they lived, instead of requiring them to travel long distances for basic treatment.

Education, too, underwent a major shift. Hundreds of new school buildings were constructed, kindergartens were introduced at scale, and classrooms were digitized. The administration emphasized skill development and employability, bringing in institutions like NIELIT, Atal Tinkering Labs, ITIs, and polytechnics to prepare students for modern job markets. Under Mission Youth and other programmes, thousands of young people received training in technology, entrepreneurship, hospitality, and creative industries. Higher education also saw significant expansion, with new colleges and university campuses being developed in districts that had long been underserved.

Economic revival became one of the defining themes of Sinha’s administration. Private investment, once almost non-existent due to security concerns, began flowing in after decades. Through a new industrial policy and global outreach, the Union Territory received investment proposals worth nearly ₹80,000 crore across sectors like IT, hospitality, manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, and renewable energy. Job-oriented infrastructure projects, including tunnels, ring roads, rural roads, and tourism facilities, created employment across regions. Programmes like Tejaswini, Mumkin, and Start-up funding schemes encouraged young entrepreneurs to build businesses instead of depending solely on government jobs.

Tourism, the backbone of the region’s economy, experienced an extraordinary revival. Record numbers of visitors arrived in Jammu and Kashmir, exploring not just traditional destinations like Gulmarg and Pahalgam but also new areas such as Gurez, Bangus, Bhaderwah, and the border belts of Kupwara and Poonch. Peace on the ground allowed the administration to host major international events, including the G-20 Working Group Meeting on Tourism in Srinagar, a landmark moment that projected Kashmir globally as a stable and welcoming destination. The revival of the film industry, through a dedicated film policy, brought cinema back to the Valley after decades, generating jobs for local youth and promoting cultural vibrancy.

An equally significant part of Sinha’s governance has been rebuilding trust. In a region carrying the burden of deep historical wounds, the administration took a compassionate approach toward victims of terrorism and violence. Public apologies, compensation, government jobs for affected families, and acknowledgment of past failures helped restore a sense of dignity among those who had long felt ignored. Communities that had faced discrimination or administrative neglect, such as Dalits, Valmikis, West Pakistani refugees, and women previously denied property rights—were given legal recognition, domicile certificates, and access to welfare schemes.

Sinha’s political style stands out because of its restraint. He does not engage in loud political battles or adversarial rhetoric. Instead, he focuses on quiet, consistent governance. This silence is strategic, it prevents polarization, keeps the administrative system stable, and allows development to remain uninterrupted by political noise. Bureaucratic decisions are now taken on merit, development projects are prioritized based on need rather than vote-bank politics, and governance has become more equitable across regions.

Through stability, policy reforms, digital transformation, security improvements, and inclusive growth, Manoj Sinha has introduced a new grammar of governance in Jammu and Kashmir. The region, once known for unrest and uncertainty, is gradually moving toward confidence and opportunity. Schools function regularly, roads reach remote villages, hospitals respond faster, tourists arrive in large numbers, and investments signal a future rooted in economic potential rather than conflict.

The idea of a “Naya Kashmir” emerging from this period is not about slogans but about practical changes, better services, stronger institutions, improved security, and a growing sense of trust between people and the administration. While challenges remain, the direction has clearly shifted from turmoil to transformation. Manoj Sinha’s tenure shows that meaningful change does not always need noise; sometimes, it is built quietly, firmly, and steadily, one reform, one village, and one citizen at a time.

Not last, but one of the longest-standing injustices in Jammu and Kashmir was the unresolved trauma of the victims of terrorism, children who lost parents, widows left without support, and families living in silence since the early 1990s. For decades, their suffering remained unacknowledged, buried under political compulsions and administrative indifference. It was only under Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha that this injustice finally began to be addressed with seriousness and compassion. By recognizing their pain, offering public apologies, ensuring compensation, and providing government jobs to the next of kin, Sinha restored dignity to thousands of families who had lived through unimaginable loss. His approach did not reduce their tragedy to a political tool; rather, it treated justice as a moral necessity. This commitment opened the hearts and minds of people across Kashmir, reminding them that the state had not forgotten them.

For many families, this was the first time in thirty years that someone in power had truly listened. Sinha’s outreach extended beyond financial support, he ensured safer housing for minority staff, addressed long-pending grievances of migrant communities, and personally met victims’ families to acknowledge their struggles. This human-centered governance created an emotional shift in Kashmir’s social landscape. Where once there was mistrust, there emerged a renewed sense of connection between citizens and the administration. The message was clear: the state stands with those who stood alone for decades.

This sincerity resonated deeply in a region long scarred by violence. It helped bridge divides, soften hardened perceptions, and bring healing into public life. In many ways, justice for terror victims became one of the most powerful symbols of the new Kashmir, where governance is not just about roads and files, but about restoring humanity, dignity, and faith in the system.

Email:---------------------vadaiekashmir@gmail.com